glennds wrote:A couple of multi-part questions if I may:

By all means! We are all here to learn from each other.

glennds wrote:1. Do you believe that the Primary Dealers could make a market for Treasury Bonds at current yields, without the Fed's intervention? If yes, then please explain why you think that.

Obviously Fed intervention is necessary in certain situations, such as a credit crisis. But all that happens is that the Fed procures overnight loans, a repo, or an swap assets with Primary Dealers if they need a little help. It's not like the Fed is doing helicopter drops.

So, to answer your question, yes. Primary Dealers are required to make a market for Treasury Bonds and they should have no trouble doing so. When things go smoothly, the money to buy Government Bonds is always available in the private sector, thanks to

previous government spending swelling reserves. This may seem hard to believe, but the money to buy Government Bonds generally comes from previous government spending (mind blowing, I know) as well as private credit that must be redistributed in the private sector in order for the private sector to remain solvent on all it's private credit to itself.

It works something like this...

Cullen Roche wrote:The Fed and Treasury are working in tandem with the Primary Dealers. As mentioned, part of the agreement in becoming a Primary Dealer is to make a market in treasuries:

“The primary dealers serve, first and foremost, as trading counterparties of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York (The New York Fed) in its implementation of monetary policy. This role includes the obligations to: (i) participate consistently as counterparty to the New York Fed in its execution of open market operations to carry out U.S. monetary policy pursuant to the direction of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC); and (ii) provide the New York Fed’s trading desk with market information and analysis helpful in the formulation and implementation of monetary policy. Primary dealers are also required to participate in all auctions of U.S. government debt and to make reasonable markets for the New York Fed when it transacts on behalf of its foreign official account-holders.”? [Source]

Therefore it is misleading to imply that the auctions might fail due to a lack of demand or some sort of funding failure. The Primary Dealers are required to make a market in government bonds. None of this means auctions can’t fail or that the US government couldn’t choose to default. It could. But that would be political folly and misunderstanding. Not due to a lack of funding.

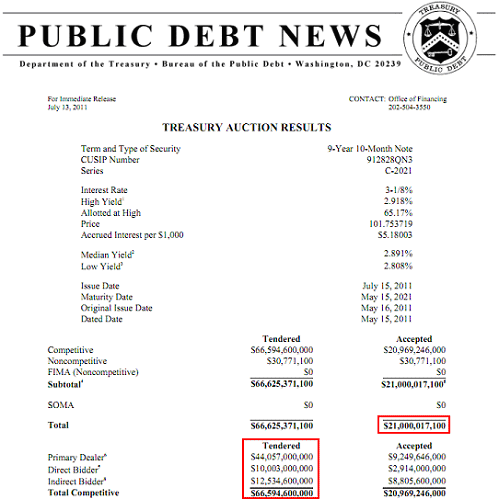

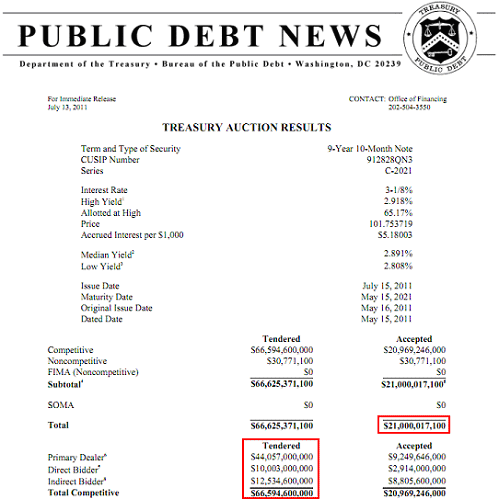

This “symbiotic relationship”? can be best seen in a recent US government 10-year bond auction. This auction occurred just weeks after QE2 ended and just before the debt-ceiling debacle occurred in July 2011 so one would have expected this to be a very unstable auction. Many prominent market pundits said the government might not be able to find buyers of the bonds. In fact, it was business as usual. As you can see below, the US government was able to auction off $21B in 10-year notes with the Primary Dealers tendering more than 2X the entire auction. Indirect bidders tendered almost half the auction, but were not needed at all to accomplish the total sales. The bid to cover at 3.1 was extremely strong.

[align=center]

[/align]

For emphasis, it’s important to understand how deficit spending occurs in this regard. Remember, government bond sales do not create the final means of payment or result in “money printing”?. Bond sales procure funds in the form of existing inside money and redistribute it to other economic agents. For simplicity, let’s take a simple example where Peter buys a bond via Treasury Direct. Peter will send the government his inside money (which was created by a private sector loan) and the government will issue Peter a government bond in exchange. The government will then redistribute Peter’s inside money to Paul who will then deposit it at a private bank. As you can see, the government simply redistributes money when it spends. Taxation is obviously even simpler as taxation is a pure redistribution of money without the bond sale. As previously mentioned, the Treasury technically settles funds in its reserve account at the Fed, but this should not confuse us on the actual flow of funds that occurs within the system.

The key distinction here is that deficit spending results in the creation of a net financial asset. That is, unlike private loan issuance, which creates both a private sector liability AND asset, government deficit spending results in no corresponding private sector liability and only a private sector asset (the government bond).

Lastly, this understanding of “inside”? and “outside”? monies exposes an important difference between the government’s balance sheet and that of private sector entities. There is no operational funding constraint for the issuer of the currency. There is a constraint to the extent that private sector entities can borrow and spend, however. So the key takeaway here is that the government balance sheet is not like a household’s or a state’s balance sheet. The US government, as an issuer of currency can never be said to be “running out of money”?.

The constraint for a currency issuer in a fiat system like the USA is never solvency, but rather inflation or real constraints (such as real resources or the output of the economy). One role of the government is to help influence the money supply and supply of financial assets so that it does not impose hardship on the private sector. The goal is always to maximize living standards of the monetary system’s users in accordance with public purpose. While growth and living standards are ultimately a byproduct of the private sector’s ability to produce and innovate, the people can utilize government and its many tools to influence the composition and quantity of the currency and financial assets. It does so via managing monetary and fiscal policy in an effort to maintain a balance between the public’s desire for net financial assets and private credit.

Source:

http://pragcap.com/understanding-the-mo ... m-part-3-2

glennds wrote:Also, if the answer is yes, then what is the purpose of the Fed's purchases?

Remember, the Fed does not directly purchase bonds from the Treasury. The Fed does not have the authority to do that (though, interestingly, Japan's BOJ does have that authority to buy government bonds directly from their Treasury. And it all works perfectly fine.). So, the Treasury auctions generally serve two purposes. First they act as a reserve drain (banks don't want excess reserves) and they allow the Fed to target interest rates. The auctions don't really "fund" the government when you really think about it.

glennds wrote:If the yields would need to increase materially to make a market among non-Fed participants, do you feel it would place any particular strain on our Federal Government to service the higher cost of debt?

Nope. To paraphrase Cullen's quote, above: There is never a solvency constraint for a fiat currency issuer, such as the United States — only inflationary constraints or real constraints (resources our output of the economy).

glennds wrote:2. Do you believe the monetary base has increased materially over the past few years if excess reserves in the banking system are included in the calculation?

I assume you mean the broad money supply. Because just looking at the monetary base and excess reserves isn't really that helpful. Excess reserves are regularly converted into Treasury Bonds (both are a private sector asset). So, reserves rise and fall with spending and auction issuance (remember, T-Bond auctions act as reserve drains). The broader money supply has certainly increased. But, keep in mind it was done to offset a huge private credit hole.

The overwhelming majority of our money supply is private credit — to the tune of roughly $57 trillion. This seems obscene at first glance, but it makes more sense when you realize that

all money (except coins) comes from either public or private debt. That's where money comes from. We live in a debt-based fiat world.

So, in reality, government spending is a pretty small in comparison to private credit and the increase in recent government spending was simply done to take the place of the private credit that was either lost or wasn't being issued during the credit crisis. Whether that was a good thing or not is certainly up for debate (I'm not arguing for or against it) but the reality is that you have to look at

total private credit

in conjunction with government spending.

glennds wrote:If yes, then what might the effect be if those excess reserves were deployed into the economy through lending and investing activities?

I'm sure someone else (moda, pointedstick or others) can answer that better than I can.

glennds wrote:Disclaimer: These are not intended to be sarcastic, rhetorical, or critical questions. I'm genuinely interested in further my understanding of what is happening around us.

Absolutely! Btw, what we are discussing is known as Monetary Realism ("MR" for short). MR simply describes how our debt-based fiat monetary system operates (i.e. no underlying political agenda). Conservatives, independents and liberals alike can all use MR to understand the operational side of our monetary system. Cullen Roche keeps a paper that he regularly refines and updates with help from those who are also trying to make sense of it all...

See:

http://pragcap.com/resources/understand ... ary-system

Cullen also takes regular questions on his blog as well. Hope that helps!

Nothing I say should be construed as advice or expertise. I am only sharing opinions which may or may not be applicable in any given case.

[/align]

[/align]